OKR Case Study: The $50K Status Report Pageant

This Fortune 500 division had great OKR training. So why weren’t their OKRs working?

What happens when you spend heavily on OKR training but your quarterly reviews are still expensive “talking circles?” This case study shows what changed when a client stopped focusing their entire OKR effort on “writing better goals” and started changing how people behave in order to improve performance.

A note before we dive in: This case study is completely anonymized—no confidential client information is shared here. And if you happen to recognize yourself in these details, please know I’m not picking on you! This pattern shows up everywhere, across organizations of all sizes and industries. I’m sharing this example because it’s such a clear illustration of what I see constantly in OKR implementations, and because the transformation this team achieved is worth celebrating and learning from!

The Problem Wasn’t the Goals (It Rarely Is)

Awhile back, I got a call from a multi-thousand person division within one of my favorite household brands (a Fortune 500 company whose name you’d know). They had invested time, money, and multiple quarters of effort into an OKR implementation that just wasn’t working.

This wasn’t some struggling startup with a DIY OKR implementation—they’d invested heavily in high-quality OKR training from a well-respected consultant (not me), and they’d built an internal center of excellence staffed with incredibly talented and dedicated experts.

They’d done everything “right” when it came to OKR creation. But they weren’t seeing the return on time or money invested that they wanted to.

This engagement had two big things going for it:

-

They allowed me to audit — by hand — multiple quarters of their objectives, key results, and attainment data. Now — when I say that I am a HUGE nerd, this is what I mean… one of my favorite things to do is manually review hundreds of OKRs and pages and pages of performance data and spot the patterns.

-

We kicked off just in time for me to actually attend and observe their quarterly OKR review, so I could audit their behavior in that meeting — which provides an absolute wealth of insight into how an organization’s performance culture is working (or isn’t).

First, I’ll share with you the result of the OKR audit — and then in a bit, we’ll talk about their OKR review behavior, and what we were able to shift (with one quarter of work) to help them get from an OKR implementation that wasn’t doing the jobs they wanted it to, to a measurably improved rhythm of business.

What did the OKR audit uncover?

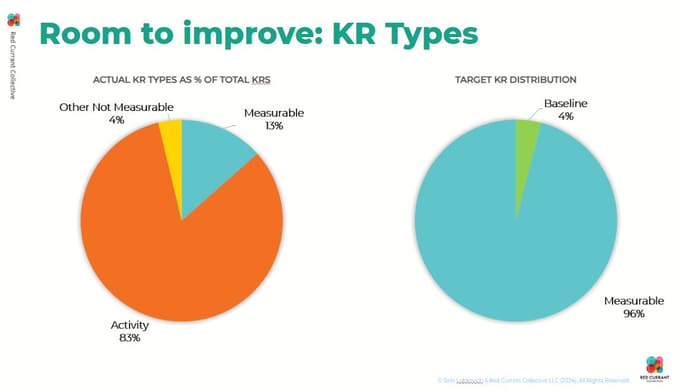

You might be shocked by this number, but it’s actually really common (and I’ve seen worse):

Just over 80% of their key results wereactivities, not measurable outcomes.

Only 13% were genuinely-measurable key results. (The remaining percentage were so ambiguously defined I couldn’t definitively categorize them either way—but they definitely weren’t measurable outcomes.)

This pattern isn’t unique to this client. I see it constantly when I audit OKR systems, regardless of how much training an organization has invested in or how sophisticated their OKR coaches are.

The question isn’t whether your team knows how to write good OKRs. The real question is: what’s making it so hard for them to actually do it?

Activity vs. Measurable Key Results: What’s the Difference?

Let me show you what I mean with a concrete example, because this distinction is at the heart of why so many OKR implementations struggle.

What do I see most often when I audit systems of key results?

Activity-focused goals like:

“Create new employee onboarding training.”

This starts with a verb—create. That makes it an activity goal, a plan, or (if you attach a date) a milestone.

A lot of teams take this a step further and add a number to make it feel more measurable.

Is this a key result?

”Complete three onboarding trainings during Q1.”

It looks like a key result because it has a number in it, right?

But quantifying activity is not the same as measuring outcomes. It’s still fundamentally a milestone—you’re tracking whether work got done, not whether that work created the impact you wanted.

What’s an example of an actually measurable key result?

”Increase new hire onboarding training rating by 20 points from 76% to 96% favorable.”

See the difference? That last one is a key result. It quantifies what actually matters—not just whether you completed the activity, but whether completing that activity created meaningful value. You’re defining what success might look like, not just identifying more work to put on the roadmap.

The vast majority of people are comfortable with activity goals and quantified activities because activity feels like it’s within our control. Those outcome-based key results, though? We can influence them, but we can’t totally control them. They’re multi-variable. They require us to be honest about what we don’t know yet and what might not work.

And that’s exactly why it’s so challenging for people to make the jump from activity-based planning to actual outcome-based key results. It takes trust, psychological safety, and a curious, learning-focused culture to work well with stretch, outcome-based key results.

Which brings us to the real barrier.

It Starts at the Top

So what was actually blocking this Fortune 500 organization from getting what they wanted from their OKR implementation?

Leader behavior.

Leaders were—inadvertently—letting all of this happen. In their quarterly business reviews, updates were all about looking good for leadership, not about learning or moving the business forward. Honest talk about misses and what the team was learning from them was rare.

I’ve seen this same pattern—I call it “success theater” or a “pageant of success”—in companies large and small, across industries and organizational structures.

Until leadership changes their expressed expectations and demonstrated behavior in OKR retrospective meetings, nothing changes in how teams approach goal-setting, no matter how good the training is.

What a $50K Status Report Pageant Actually Looks Like

In addition to auditing the OKRs themselves, in this case, I was lucky to be able to sit in on two consecutive quarterly business reviews where teams reviewed their OKR progress with leadership.

The first quarterly review?

Three sessions of up to two hours each.Seventy-seven people invited to each session.

Back-of-the-envelope math: that’s a four-to-six hour meeting that cost this organization roughly $50,000 in employee time. Just for one quarterly review cycle.

And here’s what was happening in that expensive meeting:

Almost all of the conversation was either positive or spun positive.

It was either “We got this thing done, that’s awesome” or “We didn’t get this thing done, but here’s how we’re awesome anyway.”

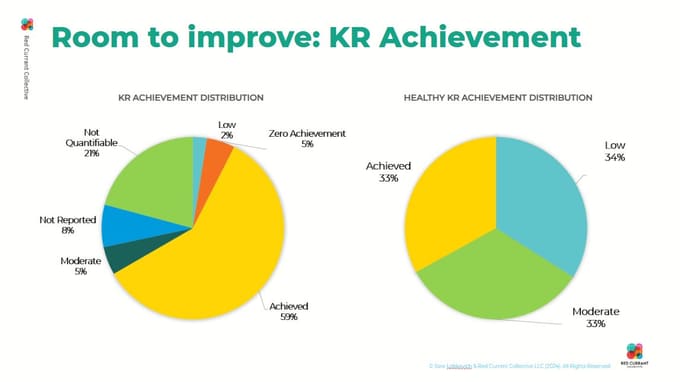

When I tallied up what actually happened in those sessions, the numbers were stark:

-

65% of updates were just someone saying “We finished that key result”—not sharing what they learned, not discussing impact, just reporting that something was done

-

Only 8% of updates included honest, transparent discussion where someone said a goal wasn’t met and explained why

-

Only 10% of speakers who had a miss actually voiced a need or dependency that was blocking their progress

-

Only 10% of speakers received a question about the quarter that had just passed

-

Only 20% of speakers received a question about the quarter ahead

Important risks and opportunities for improvement were getting lost in the noise because teams felt this quarterly review was their one chance to get in front of leadership and look good — and the meeting structure itself was reinforcing that behavior.

Nobody was asking about actual outcomes. Nobody was asking what people needed. The conversation was entirely focused on activity: why didn’t this task get done, what tasks are you doing next quarter, when will those tasks be finished?

This is what I mean when I say the problem isn’t your goals. This organization had invested heavily in teaching people to write better OKRs. But the way their quarterly OKR review meetings were structured was systematically teaching everyone that what leadership actually cared about was looking successful, not learning or improving.

OKR Case Study:

How We Redesigned the Quarterly Business Review

We eliminated the pageant of successfulness and refocused the quarterly review on what actually matters: learnings, blockers, risks, needs, and opportunities.

The new rule was simple: Only discuss OKRs that have a learning, blocker, risk, need, or opportunity.

If a team had met their key result and everything was on track with no blockers or learnings to share, they didn’t need to present.

That might sound radical, but think about it—if you’re already tracking OKR progress in a dashboard or regular status updates, why do you need to spend meeting time on “everything’s fine, we’re on track”? That’s what dashboards are for.

Meeting time—especially expensive meeting time with 77 senior people in the room—should be reserved for the conversations that actually need to happen. The places where people need help, where there’s a risk that needs attention, where there’s a learning that could benefit other teams.

But here’s the crucial part, the piece that most organizations miss when they try to redesign their OKR retrospective process: We focused on leader behavior change first, before rolling out the new meeting format.

It’s easy to tell teams “come prepared to share your risks and needs instead of celebrating your wins.” It’s much harder to create an environment where teams actually feel safe doing that. And that safety comes from leader behavior, not from revised meeting guidelines.

Before the organization went into their next quarterly business review, senior leadership reviewed and committed to specific behaviors they were going to practice:

-

Ask about results and outcomes, not about activity and tasks

-

When people voice challenges, focus on what they need (not on why they didn’t get it done)

-

Stay calm and curious about poor performance on key results (no reactive responses, no “seagulling” behavior where a leader swoops in to micromanage the details)

-

Ask questions that help teams problem-solve , not questions that put teams on the defensive

The leadership team did a phenomenal job with this behavior change. They came to that meeting ready to model the new approach, and they made it clear through their behavior—not just their words—that it was safe for teams to prioritize truth over the appearance of accomplishment.

The Results: When OKR Review Meetings Actually Work

Meeting time was cut from four hours to one hour —over 70% reduction in time spent.

The number of individual topics discussed dropped by 60% —which meant significantly more time for each important topic to actually get discussed, not just reported on. Teams were having real conversations about what they needed and how to move forward, not just delivering four-minute status updates and leaving the stage.

Real risks and opportunities were surfaced and addressed in the moment, instead of getting buried in the noise of celebration and spin.

And perhaps most importantly, the meeting shifted from reporting to problem-solving.

Teams started asking each other questions. Leaders were focused on removing roadblocks rather than dwelling on misses. The psychological safety to share bad news (alongside the good) increased measurably, because the leader behavior in the room demonstrated that honest conversation was valued more than looking successful.

This didn’t erase accountability—managers still held their teams to the milestones and delivery commitments in their regular operating rhythm. But separating the OKR review meeting from the status report meeting created space for the kind of strategic, cross-functional problem-solving that OKRs are supposed to enable in the first place.

Which Side Are You On?

Here’s the real question: Do you want your OKRs to look good in a dashboard, or do you want them to drive actual results?

This Fortune 500 case study demonstrates something I see across organizations of all sizes: writing better goals won’t matter if your OKR meeting structure and leader behavior stay the same.

True transformation in an OKR implementation doesn’t come from better goal-writing training. It comes from changing how goals are reviewed, discussed, and acted on—which means changing how leaders behave in those review meetings.

When leaders demonstrate through their behavior (not just their words) that they value learning over looking good, that they’re focused on removing blockers rather than assigning blame, and that honest conversation about misses is more valuable than spinning everything positive—that’s when teams start writing real outcome-based key results instead of activity lists dressed up as goals.

The meeting structure matters. The questions leaders ask matter. The way leaders respond to misses and challenges matters. All of it shapes whether your OKR implementation becomes a tool for real strategic progress or just another compliance exercise.

Want OKRs That Drive Results?

If you’re tired of OKR implementations that look good on paper but don’t create real strategic alignment or results, you’re not alone. The good news is that the path forward doesn’t require starting over or investing in more training. It requires changing how you use OKR review meetings and how your leaders behave in those meetings.

For more real-world OKR case studies—actual situations from client work, not just theory—grab access to my No-BS OKRs private podcast. It’s six focused episodes packed with field-tested stories and practical approaches I use with clients globally, after training over 2,000 OKR coaches and working with hundreds of organizations. (It’s also soon-to-be a sneak peek of the audiobook version of my book!)

Or pick up a copy of You Are a Strategist: Use No-BS OKRs to Get Big Things Done to learn the full framework for creating and implementing OKRs that actually drive results instead of just generating more meetings and dashboards.

Frequently-Asked Questions:

Making OKR Review Meetings Actually Work

-

Q: How do you get leadership to agree to focus on behavior change before changing the meeting format?

A: Show them the data. In this case, when leaders saw the quantified analysis of what was actually happening in their quarterly reviews—65% of updates were just “we finished this,” only 8% included honest discussion of why something didn’t work—it made the case for change immediately clear. Leaders want their meetings to be effective. When you can show them concrete evidence that the current approach isn’t working, they’re generally very receptive to trying something different.

-

Q: What if teams don’t have anything to discuss because everything’s on track? Don’t you need to know that things are going well?

A: That’s what dashboards and regular status updates are for. If your OKR system is set up well, leadership should already have visibility into what’s on track and what’s not before they walk into a quarterly business review. The meeting time should be reserved for the conversations that need to happen—the places where teams need help, where strategy needs to be adjusted, where there’s cross-functional coordination required. “Everything’s fine” doesn’t need meeting time. Celebrating wins does — but every “we’re in the green” doesn’t merit a party when time, capacity, and resources are finite.

-

Q: How do you train teams to identify what’s worth bringing to the quarterly review vs. what can be handled elsewhere?

A: We coach teams to ask themselves: Is there a learning here that would benefit other teams? Is there a blocker or dependency that needs senior leadership attention or cross-functional coordination to resolve? Is there a risk that could affect our ability to meet this OKR? If yes to any of those, bring it to the quarterly review. If it’s just a status update or a problem the team can solve within their normal operating rhythm, handle it there instead.

-

Q: What about celebrating wins? Isn’t it important for team morale to recognize accomplishments?

A: Absolutely. But there are much more effective ways to celebrate wins than in minutes-long updates in a 77-person multiple-hour quarterly business review meeting. Celebrate wins in team meetings, in company-wide communications, in one-on-ones. Reserve the expensive, high-level strategic meeting time for the work that actually requires that many senior people in the room together.

-

Q: How long does it take for this kind of behavior change to stick?

A: In this case, we saw meaningful change in the very first redesigned quarterly review, because the leadership team committed to the new behaviors and practiced them consistently throughout that meeting. But it typically takes 2-3 cycles before teams fully trust that the new approach is real and not just a temporary experiment. Consistency in leader behavior is key—if leaders revert to old patterns even once or twice, teams will quickly default back to the “looking good” mode.

-

Q: Can this approach work in smaller organizations, or is it only for large companies with formalized OKR systems?

A: The principles work at any scale. I’ve seen similar patterns in organizations with <10 people and Fortune 100s. The size of the company and meeting might be different, but the fundamental dynamic is the same: when review meetings focus on status reporting and looking good rather than on problem-solving and learning, teams will write activity-based goals instead of outcome-based key results. Changing leader behavior in those review meetings changes how teams approach goal-setting, regardless of organization size.

The difference between successful OKR implementations and expensive compliance and progress performances?

It starts with designing for the right behaviors—from leadership—on day one.

Sara Lobkovich is an OKR coach, strategy facilitator, and author who specializes in helping mid-market organizations turn strategy into everyday action and results. She’s trained over 2,000 OKR coaches across 300+ organizations globally and is known for her “No-BS OKRs” approach that focuses on behavior change and learning, not just better goal-writing.

You Are a Strategist: Use No-BS OKRs to Get Big Things Done

The practical guide to setting direction, making real progress, and clarifying priorities you and your collaborators can trust.

Get the Book

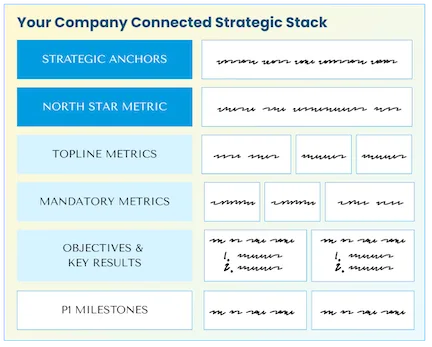

The Connected Strategic Stack

Bridge the gap between vision and results with a one-page strategy you'll actually use.

DOWNLOAD AN EXAMPLE STACK →